Airfix: DE HAVILLAND VAMPIRE F.3 1:48 m/Norske merker.

kr545.00 inkl. mva

Plastbyggesett i skala 1:48

Til dette byggesettet trenger du lim, pensel og maling.

På lager .

De Havilland Vampire F.3 1:48

With the magnificent de Havilland Mosquito only just entering Royal Air Force service towards the end of 1941, designers at the company were next asked to turn their attentions to developing a new jet engine, one which was capable of powering a new generation of high speed fighter aircraft. Entrusted to the brilliant mind of engine designer Frank Halford, he was determined that his engine would be less complicated and of simpler design than the one being developed by his rival, Frank Whittle and he was ready to test his engine by April 1942. Showing great promise and producing the intended level of thrust, the only thing to do now was to see how it performed in the air.

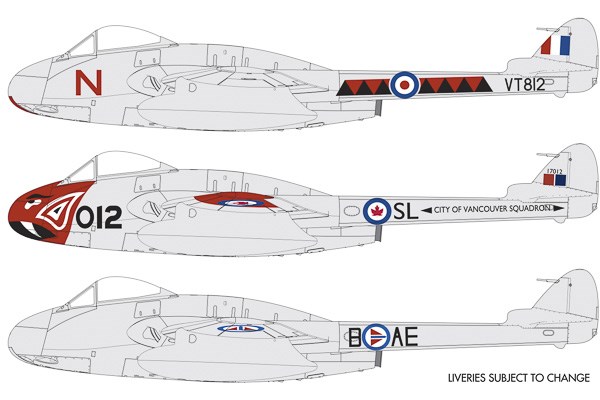

Schemes

‘A06107’ C – de Havilland D.H.100 Vampire F.3 P42408/AE-B, Norwegian Air Force, Gardermoen Museum, Oslo, Norway, 2019

C – de Havilland D.H.100 Vampire F.3 P42408/AE-B, Norwegian Air Force, Gardermoen Museum, Oslo, Norway, 2019

‘A06107’ B – de Havilland D.H.100 Vampire F.3 17018, No.442 ‘City of Vancouver’ Auxiliary Fighter Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force Station Vancouver, Canada, 1949

B – de Havilland D.H.100 Vampire F.3 17018, No.442 ‘City of Vancouver’ Auxiliary Fighter Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force Station Vancouver, Canada, 1949

‘A06107’ A – de Havilland D.H.100 Vampire F.3 VT812/N, No.601 Squadron, Royal Auxiliary Air Force, North Weald, Essex, England 1952

A – de Havilland D.H.100 Vampire F.3 VT812/N, No.601 Squadron, Royal Auxiliary Air Force, North Weald, Essex, England 1952

At a time when jet engine technology was still in its infancy and these early engines were both a little lacking in power and slow to respond to power input commands, de Havilland’s decision to produce their first jet aircraft as a single engined design was a brave one and placed great faith in the performance of their new jet engine. The diminutive new aircraft was initially designated de Havilland DH.100 ‘Spider Crab’, with this codename used to mask the secret nature of the aircraft’s development. Constructed around the new de Havilland Goblin 1 turbojet, the aircraft featured a relatively short, egg shaped central fuselage nacelle and employed a unique twin-boom tail configuration for control stability which allowed the engine’â„¢s thrust to egress directly from the central fuselage. With a requirement to take the pressure off the wartime aviation industry, this experimental aircraft had to be constructed of both wood and metal and it is interesting to note that the majority of the fuselage employed the same laminated plywood construction the company had perfected during Mosquito production.

Unfortunately for the de Havilland team working on the new jet, their Mosquito was proving to be such a war winner that this experimental project was deemed of lesser importance than producing Mosquitos, probably rightly so for Britain’s war effort. To rub salt into this aviation wound, the first flight of the aircraft would be further delayed for an unbelievable reason – the only serviceable jet engine was ordered to be sent to America to help with the advancement of their own jet powered project. Mosquito production priority and a series of unforeseen delays eventually dictated that the Gloster Meteor’s development outpaced that of its de Havilland competitor, with the Meteor taking the honour of being Britain’s first jet aircraft to enter service and the only Allied jet of WWII.

Making its first flight on 20th September 1943, de Havilland DH.100 ‘Spider Crab’ LZ548/G took off from the company’s Hatfield airfield in the hands of chief test pilot Geoffrey de Havilland Jr. Interestingly, the ‘G’ used in the identification code highlights the secret nature of the project and required that the aircraft must be guarded at all times whilst on the ground. This first flight lasted just over 30 minutes, during which time the aircraft exceeded 400mph and showed great promise, however, it would be April 1945 before a production aircraft would take to the air, by which time the new jet fighter had been christened the Vampire. Despite its protracted development, Britain’s second jet fighter to enter service would prove to be something of a classic and is now regarded as one of the most successful early jet aircraft in the world.

The Vampire F.Mk.I entered Royal Air Force service in March 1946, to be followed by the revised and more capable F.3 just two years later. The Vampire F.3 was basically a longer range version of its predecessor, featuring increased internal fuel capacity and the ability to carry two external fuel tanks. This latest variant also differed visually, in that it incorporated taller and more rounded vertical stabilisers, a lowered horizontal stabiliser and distinctive ‘acorn’ fairings at the base of each vertical stabiliser. Although this was still relatively new technology, de Havilland cleverly designed the aircraft to be simple to maintain and operate, earning the aircraft an enviable reputation for reliability amongst air and ground crews alike and allowing more pilots to safely make the transition to jet powered flight.

With a number of significant firsts to its name, the Vampire was the first RAF aircraft to exceed 500 mph, with the extra range of the F.3 allowing this to be the first jet fighter to cross the Atlantic. The Vampire F.3’s of No.32 Squadron were also the first RAF jet fighters to be deployed outside Northwest Europe and the first to operate in the higher temperatures of the Mediterranean. Without doubt, the de Havilland Vampire has to be considered one of the most important early jet fighters in the world.